In September, Ms. Merkel is expected to win a third term as chancellor. That means her agenda will dominate Europe's crisis response for years. The euro's survival hinges to a considerable extent on whether her strategy works. Her approach is to put the onus on struggling nations to save the euro by cutting their budget deficits, labor costs and welfare. It is a strategy that is as popular in Germany as it is divisive in Europe's weakest countries. Critics warn that years more of such cuts could do lasting damage to the economies, social fabric and political stability of weak nations. "The depression that is being imposed on these countries may last quite a long time," says Paul De Grauwe, professor at the London School of Economics and one of Europe's most prominent economists. "The perception of Germany is deteriorating," he says.

Germans trust Ms. Merkel more than any other politician to save the euro and protect German taxpayers' money. However, if the euro zone's recession starts to sting in Germany more than it has so far, pressure could build on Ms. Merkel to rethink her approach. Some observers say Berlin might consider stimulating growth through a public investment program after the election. But analysts generally agree: Europe shouldn't hold its breath.

Ms. Merkel, a 58-year-old former theoretical physicist, is convinced she is guiding Europe toward redemption. Weaning governments from debt and eliminating risks—such as Cyprus's outsize banks, a major target of the controversial Cyprus bailout—is bound to cause hardship, her advisers say. She declined to be interviewed. Yet even southern European politicians who agree with Ms. Merkel that their countries must reform say Germany needs to do more to revive growth. "We need a convergence. Berlin has to understand the arguments of the South more, and the South has to understand Berlin's arguments more," says Greece's finance minister, Yannis Stournaras.

Mutual understanding is more elusive than ever. Cypriot protesters, shocked at Berlin's statements that their banking industry was "unsustainable," portrayed Ms. Merkel in Nazi garb. The Cyprus bailout—which left people there unable to fully access their bank accounts—has been criticized across much of Europe for the pain it inflicts locally. But ever since 2010's Greek bailout, Ms. Merkel has sought to prevent euro-zone countries from becoming liabilities for Germany, which joined the euro on the promise that it would be a club of self-reliant nations. Ms. Merkel's early idea backfired. She wanted bond investors to lose money in future bailouts. Her advisers believed this would encourage investors to lend more carefully and press indebted countries to fix their mess.

The ECB warned that steps like these might frighten investors from lending to weaker governments. And so it proved. By late 2011, capital flight threatened the whole of southern Europe. But Germany itself remained an island of calm. Ms. Merkel faced no domestic pressure to change course. Instead, she and her advisers worked on a new architecture for the euro zone. She hoped to get ahead of events and attack root problems. "It cannot be that we let the markets drive us," she told officials at the chancellery in mid-2011.

She and her aides saw three root causes. Many euro members had become uncompetitive by neglecting to overhaul their labor markets, business regulation and other areas. The 2008 crash had pushed some countries' debt to the limit of what they could finance. And nations including Cyprus had let their banks take too many risks.

In summer 2011, Ms. Merkel's key Europe adviser, Nikolaus Meyer-Landrut, distilled the thinking to a chart on a single sheet of paper. The chart divided euro-zone economic policies into two groups: Those made by individual national governments, such as taxes, labor laws and pension systems, and those handled by the EU's "supranational" central bodies, including trade and antitrust rules. Europe's troubles, the chart suggested, arose from policy areas controlled by national governments. Centralizing the national policies was politically unrealistic—akin to creating a United States of Europe. The chart suggested another path: Leave the policies with the national governments, but "coordinate" them via new, and binding, rules and pacts.

The diagnosis showed how German thinking was diverging from the widespread international view of the euro-zone crisis. It put all blame on debtor nations. Most observers outside Germany see a more collective failure that needs a collective solution: a deeper economic union. That would entail shared, pan-European budgets to smooth economic downturns and support ailing banks, and a degree of common borrowing, as well as a bolder central bank.

In 2012, a Europe chafing at Ms. Merkel's strictures pushed back. As Spanish banks stumbled, Germany insisted that Spain's government had to borrow up to €100 billion to shore them up. Markets reacted badly. So in June 2012, Spain, France and Italy pressed Ms. Merkel to accept a "banking union"—using Europe's collective financial muscle to relieve weaker states of the burden of rescuing banks. Under pressure, Ms. Merkel agreed that the euro zone's bailout fund, the European Stability Mechanism or ESM, could "have the possibility to recapitalize banks directly" once the euro zone had created a common banking supervisor.

As the rest of Europe understood it, Germany had finally agreed that the euro zone needed to pool its strength. But German lawmakers were in uproar over Ms. Merkel's apparent surrender. Germany quickly punctured hopes that it would save other countries' banks. "The South thought that all countries could now shift the burden of dealing with all of their banking problems onto the ESM," said a German official. "It was a pure chimera." Around then, in mid-2012, Europe also faced Greek political chaos. Many in Germany's governing coalition doubted Greece was capable of staying in the euro. Officials spoke of the "infected leg theory"—the gangrenous Greek limb had to be amputated to save the body of the euro.

Past missteps had taught Ms. Merkel to reckon with financial-market chain reactions. Separately she called Bundesbank President Jens Weidmann and German ECB executive-board member Jörg Asmussen to ask what would happen if Greece left. Both said Cyprus would probably leave, too. What then, Ms. Merkel wanted to know: How many dominoes would fall? Mr. Asmussen said there was no way of knowing. For Ms. Merkel, that was too uncertain. Mr. Weidmann agreed—but added that keeping Greece in the euro would also be risky if Greece couldn't keep its reform commitments.

Ms. Merkel needed a reliable partner in Athens.

Greece's visibly tense premier, Antonis Samaras, visited Berlin in August and tried hard to persuade Ms. Merkel he could turn his country around. He had practiced his pitch for hours in his hotel. "I can guarantee you, we will work day and night," Mr. Samaras said. Ms. Merkel decided he deserved her support, provided that he enacted overhauls. "If there is good progress, I would consider visiting Athens," she told him. Her trip to Greece a few weeks later demonstrated publicly that she was betting on him. But Greece's finances were badly off track. The IMF said it would continue to lend only if Europe forgave some of its loans to Greece. That was politically toxic for Ms. Merkel.

Germany's finance minister, Wolfgang Schäuble, tried to broker a solution. At secret Paris talks on Nov. 19 between IMF and EU officials, he offered to cut Greek-loan interest to the bone. And, he said, Europe could forgive some of Greece's debt after 2014 if it completed its reforms. Ms. Merkel upbraided him the next morning. He had gone too far, she said. Until now, they could say Germany was losing no money on bailouts, she said. "But this would be a loss for German taxpayers. I can't sell this," she said. Greece's interest rate could be cut, but not below Germany's own borrowing costs, she said. Her veto sent European and IMF officials back to the drawing board. They cobbled together a plan to stabilize Greece's debt by 2022. The math adds up only because of vague footnotes citing future "further measures." Germany denies that means debt forgiveness.

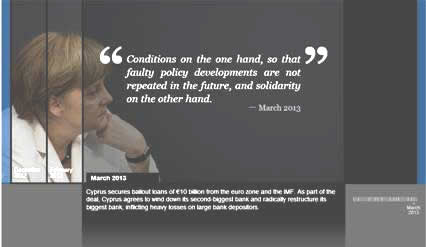

The chancellor's handling of Greece and the "banking union" clarified German positions. Bailed-out euro members must repay their aid. And they must support their own banks. Cyprus couldn't do both. Germany refused to lend Cyprus more than the IMF said could be repaid. And it insisted direct ESM investments in banks weren't possible yet. That meant Cyprus could stay afloat only by impounding bank deposits. After Cyprus's parliament rejected Europe's first plan on March 19, President Anastasiades scrambled for a way to save his banks. His government considered tapping the country's pension funds.

Ms. Merkel shot that down in a March 22 meeting with Bundestag lawmakers. Cyprus was trying to "test" Europe and refused to see that its banking "business model" was finished, she said, according to people present. Two days later, Cyprus gave in to German and IMF demands to shrink its banks radically, inflicting drastic losses on large depositors.

Ms. Merkel didn't want such euro-zone dominance. She knew how uneasy it would make Germany and Europe alike. "Germany is in a difficult position," Ms. Merkel told The Wall Street Journal in an unusually frank moment in 2009, as Europe's debt crisis was just beginning. "If we do too much, we dominate. If we do too little, we're criticized" for not leading, she said. "I will always make sure that one big country isn't issuing directives." |